Dr Seuss Clip Art Cat in the Hat Dr Seuss Cartoon Characters Drawings of Portait

| Dr. Seuss | |

|---|---|

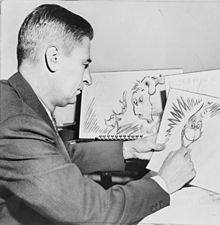

Dr. Seuss in Apr 1957 | |

| Born | Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-03-02)March ii, 1904 Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 24, 1991(1991-09-24) (aged 87) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Teaching |

|

| Genre | Children'south literature |

| Years active | 1921–1990[one] |

| Spouse | Helen Palmer (one thousand. 1927; died 1967) Audrey Rock Dimond (g. 1968) |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

| world wide web | |

Theodor Seuss Geisel (;[ii] [iii] [4] March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991)[v] was an American children'south author, political cartoonist, illustrator, poet, animator, and filmmaker. He is known for his work writing and illustrating more than 60 books under the pen name Dr. Seuss (,[4] [half dozen]). His piece of work includes many of the near pop children's books of all time, selling over 600 one thousand thousand copies and beingness translated into more twenty languages by the time of his expiry.[7]

Geisel adopted the name "Dr. Seuss" as an undergraduate at Dartmouth College and every bit a graduate student at Lincoln College, Oxford. He left Oxford in 1927 to begin his career as an illustrator and cartoonist for Vanity Fair, Life, and diverse other publications. He besides worked as an illustrator for advertizement campaigns, most notably for FLIT and Standard Oil, and equally a political cartoonist for the New York newspaper PM. He published his beginning children'south book And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street in 1937. During Earth War II, he took a brief hiatus from children'due south literature to illustrate political cartoons, and he besides worked in the animation and motion-picture show section of the The states Regular army where he wrote, produced or animated many productions including Design for Decease, which later won the 1947 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[8]

After the state of war, Geisel returned to writing children's books, writing classics like If I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1955), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), Dark-green Eggs and Ham (1960), One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1960), The Sneetches (1961), The Lorax (1971), The Butter Battle Book (1981), and Oh, the Places You'll Go (1990). He published over 60 books during his career, which have spawned numerous adaptations, including eleven television specials, five feature films, a Broadway musical, and four goggle box series.

Geisel won the Lewis Carroll Shelf Laurels in 1958 for Horton Hatches the Egg and again in 1961 for And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Geisel's altogether, March two, has been adopted equally the annual date for National Read Across America 24-hour interval, an initiative on reading created by the National Instruction Clan. He also received two Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Children'due south Special for Halloween is Grinch Night (1978) and Outstanding Animated Program for The Grinch Grinches the True cat in the Hat (1982).[ix]

Life and career

Early on years

Geisel was built-in and raised in Springfield, Massachusetts, the son of Henrietta (née Seuss) and Theodor Robert Geisel.[ten] [xi] His father managed the family brewery and was afterwards appointed to supervise Springfield's public park system past Mayor John A. Denison[12] after the brewery closed because of Prohibition.[13] Mulberry Street in Springfield, made famous in his first children's book And to Think That I Saw Information technology on Mulberry Street, is near his boyhood dwelling on Fairfield Street.[14] The family unit was of German descent, and Geisel and his sister Marnie experienced anti-German language prejudice from other children following the outbreak of Earth War I in 1914.[15] Geisel was raised as a Missouri Synod Lutheran and remained in the denomination his entire life.[16]

Geisel attended Dartmouth College, graduating in 1925.[17] At Dartmouth, he joined the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity[10] and the humor magazine Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, eventually ascension to the rank of editor-in-main.[ten] While at Dartmouth, he was caught drinking gin with nine friends in his room.[eighteen] At the time, the possession and consumption of alcohol was illegal under Prohibition laws, which remained in identify between 1920 and 1933. As a result of this infraction, Dean Chicken Laycock insisted that Geisel resign from all extracurricular activities, including the Jack-O-Lantern.[19] To continue working on the magazine without the assistants's cognition, Geisel began signing his piece of work with the pen name "Seuss". He was encouraged in his writing past professor of rhetoric W. Benfield Pressey, whom he described as his "big inspiration for writing" at Dartmouth.[xx]

Upon graduating from Dartmouth, he entered Lincoln Higher, Oxford, intending to earn a Medico of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in English literature.[21] [22] At Oxford, he met his hereafter married woman Helen Palmer, who encouraged him to give up condign an English teacher in favor of pursuing drawing every bit a career.[21] She later recalled that "Ted'south notebooks were always filled with these fabulous animals. So I prepare to work diverting him; here was a man who could draw such pictures; he should exist earning a living doing that."[21]

Early career

Geisel left Oxford without earning a degree and returned to the Usa in February 1927,[23] where he immediately began submitting writings and drawings to magazines, book publishers, and advertising agencies.[24] Making use of his time in Europe, he pitched a series of cartoons called Eminent Europeans to Life magazine, but the mag passed on information technology. His first nationally published drawing appeared in the July 16, 1927, outcome of The Sabbatum Evening Mail service. This single $25 sale encouraged Geisel to motility from Springfield to New York City.[25] Subsequently that twelvemonth, Geisel accepted a job as writer and illustrator at the sense of humor magazine Estimate, and he felt financially stable enough to marry Palmer.[26] His first cartoon for Judge appeared on October 22, 1927, and Geisel and Palmer were married on November 29. Geisel's first work signed "Dr. Seuss" was published in Judge virtually 6 months later he started working in that location.[27]

In early on 1928, one of Geisel's cartoons for Judge mentioned Waltz, a mutual bug spray at the fourth dimension manufactured by Standard Oil of New Jersey.[28] Co-ordinate to Geisel, the married woman of an advertising executive in accuse of advertizement Flit saw Geisel'southward drawing at a barber's and urged her husband to sign him.[29] Geisel'southward beginning Flit ad appeared on May 31, 1928, and the entrada continued sporadically until 1941. The campaign's catchphrase "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" became a part of popular civilisation. It spawned a song and was used as a punch line for comedians such as Fred Allen and Jack Benny. As Geisel gained notoriety for the Flit campaign, his work was in demand and began to appear regularly in magazines such as Life, Liberty, and Vanity Fair.[30]

The coin Geisel earned from his advertising work and mag submissions made him wealthier than even his most successful Dartmouth classmates.[30] The increased income allowed the Geisels to motility to better quarters and to socialize in higher social circles.[31] They became friends with the wealthy family of broker Frank A. Vanderlip. They also traveled extensively: by 1936, Geisel and his wife had visited xxx countries together. They did not take children, neither kept regular role hours, and they had ample money. Geisel besides felt that traveling helped his creativity.[32]

Geisel's success with the Flit entrada led to more advertising work, including for other Standard Oil products like Essomarine boat fuel and Essolube Motor Oil and for other companies like the Ford Motor Company, NBC Radio Network, and Holly Sugar.[33] His commencement foray into books, Boners, a drove of children's sayings that he illustrated, was published by Viking Press in 1931. It topped The New York Times non-fiction bestseller list and led to a sequel, More than Boners, published the aforementioned year. Encouraged past the books' sales and positive disquisitional reception, Geisel wrote and illustrated an ABC volume featuring "very strange animals" that failed to involvement publishers.[34]

In 1936, Geisel and his wife were returning from an ocean voyage to Europe when the rhythm of the ship'southward engines inspired the poem that became his first children's book: And to Recollect That I Saw Information technology on Mulberry Street.[35] Based on Geisel's varied accounts, the book was rejected by between 20 and 43 publishers.[36] [37] According to Geisel, he was walking home to burn down the manuscript when a adventure run into with an old Dartmouth classmate led to its publication by Vanguard Press.[38] Geisel wrote four more books before the United states of america entered World War Ii. This included The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins in 1938, equally well equally The King'south Stilts and The Seven Lady Godivas in 1939, all of which were in prose, atypically for him. This was followed by Horton Hatches the Egg in 1940, in which Geisel returned to the use of poetry.

Globe State of war Ii-era work

"The Goldbrick", Private Snafu episode written by Geisel, 1943

As World War II began, Geisel turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in ii years as editorial cartoonist for the left-leaning New York City daily newspaper, PM.[39] Geisel's political cartoons, later published in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, denounced Hitler and Mussolini and were highly disquisitional of non-interventionists ("isolationists"), most notably Charles Lindbergh, who opposed US entry into the state of war.[40] One cartoon[41] depicted Japanese Americans being handed TNT in anticipation of a "bespeak from home", while other cartoons deplored the racism at home against Jews and blacks that harmed the state of war effort.[42] [43] His cartoons were strongly supportive of President Roosevelt's handling of the war, combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war effort with frequent attacks on Congress[44] (especially the Republican Party),[45] parts of the press (such as the New York Daily News, Chicago Tribune, and Washington Times-Herald),[46] and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union,[47] [48] investigation of suspected Communists,[49] and other offences that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently.

In 1942, Geisel turned his energies to directly support of the U.South. war attempt. Showtime, he worked cartoon posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. Then, in 1943, he joined the Ground forces as a helm and was commander of the Blitheness Department of the Offset Motility Moving-picture show Unit of the U.s.a. Regular army Air Forces, where he wrote films that included Your Job in Germany, a 1945 propaganda film nearly peace in Europe after Globe War II; Our Job in Nihon; and the Private Snafu series of adult army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the Legion of Merit.[50] Our Job in Nippon became the basis for the commercially released flick Design for Death (1947), a study of Japanese culture that won the Academy Accolade for All-time Documentary Feature.[51] Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950) was based on an original story by Seuss and won the University Honour for Best Animated Brusk Film.[52]

Later on years

After the state of war, Geisel and his married woman moved to the La Jolla community of San Diego, California, where he returned to writing children's books. He published nearly of his books through Random House in North America and William Collins, Sons (later HarperCollins) internationally. He wrote many, including such favorites every bit If I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), and Light-green Eggs and Ham (1960). He received numerous awards throughout his career, but he won neither the Caldecott Medal nor the Newbery Medal. Three of his titles from this period were, however, chosen every bit Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Award books): McElligot'south Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950). Dr. Seuss also wrote the musical and fantasy film The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T., which was released in 1953. The movie was a critical and financial failure, and Geisel never attempted some other feature moving picture. During the 1950s, he also published a number of illustrated short stories, mostly in Redbook mag. Some of these were afterwards collected (in volumes such every bit The Sneetches and Other Stories) or reworked into independent books (If I Ran the Zoo). A number have never been reprinted since their original appearances.

In May 1954, Life published a report on illiteracy amongst school children which concluded that children were not learning to read because their books were boring. William Ellsworth Spaulding was the director of the instruction division at Houghton Mifflin (he later became its chairman), and he compiled a listing of 348 words that he felt were important for first-graders to recognize. He asked Geisel to cut the list to 250 words and to write a book using only those words.[53] Spaulding challenged Geisel to "bring back a book children can't put down".[54] Ix months later, Geisel completed The True cat in the Hat, using 236 of the words given to him. It retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Geisel's before works but, because of its simplified vocabulary, information technology could be read past beginning readers. The Cat in the Hat and subsequent books written for young children accomplished significant international success and they remain very pop today. For example, in 2009, Green Eggs and Ham sold 540,000 copies, The Cat in the Hat sold 452,000 copies, and One Fish, 2 Fish, Crimson Fish, Bluish Fish (1960) sold 409,000 copies—all outselling the majority of newly published children's books.[55]

Geisel went on to write many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary manner (sold every bit Beginner Books) and in his older, more elaborate style.

In 1955, Dartmouth awarded Geisel an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters, with the citation:

Creator and fancier of fanciful beasts, your affinity for flying elephants and man-eating mosquitoes makes u.s. rejoice you were not around to be Director of Admissions on Mr. Noah'due south ark. Only our rejoicing in your career is far more positive: every bit author and artist yous singlehandedly have stood every bit St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day. At that place was an inimitable wriggle in your piece of work long before y'all became a producer of movement pictures and animated cartoons and, as e'er with the best of humor, behind the fun there has been intelligence, kindness, and a feel for humankind. An Academy Award winner and holder of the Legion of Merit for war film work, you accept stood these many years in the academic shadow of your learned friend Dr. Seuss; and because we are certain the time has come when the skilful physician would want y'all to walk past his side every bit a full equal and considering your College delights to acknowledge the distinction of a loyal son, Dartmouth confers on you her Doctorate of Humane Messages.[56]

Geisel joked that he would now have to sign "Dr. Dr. Seuss".[57] His wife was sick at the fourth dimension, then he delayed accepting information technology until June 1956.[58]

On Apr 28, 1958, Geisel appeared on an episode of the console game bear witness To Tell the Truth.[59]

Geisel's wife Helen had a long struggle with illnesses. On October 23, 1967, Helen died by suicide; Geisel married Audrey Dimond on June 21, 1968.[60] Although he devoted most of his life to writing children's books, Geisel had no children of his own, maxim of children: "Y'all have 'em; I'll entertain 'em."[sixty] Dimond added that Geisel "lived his whole life without children and he was very happy without children."[60] Audrey oversaw Geisel'southward manor until her death on December 19, 2018, at the age of 97.[61]

Geisel was awarded an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters (50.H.D.) from Whittier College in 1980.[62] He also received the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal from the professional children'southward librarians in 1980, recognizing his "substantial and lasting contributions to children'southward literature". At the time, information technology was awarded every five years.[63] He won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1984 citing his "contribution over most half a century to the instruction and enjoyment of America'south children and their parents".[64]

Illness, death, and posthumous honors

Geisel died of cancer on September 24, 1991, at his dwelling house in the La Jolla community of San Diego at the age of 87.[21] [65] His ashes were scattered in the Pacific Sea. On Dec 1, 1995, four years after his death, University of California, San Diego's University Library Building was renamed Geisel Library in honor of Geisel and Audrey for the generous contributions that they made to the library and their devotion to improving literacy.[66]

While Geisel was living in La Jolla, the United States Postal Service and others often confused him with swain La Jolla resident Dr. Hans Suess, a noted nuclear physicist.[67]

In 2002, the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden opened in Springfield, Massachusetts, featuring sculptures of Geisel and of many of his characters.

In 2017, the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum opened adjacent to the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden in the Springfield Museums Quadrangle.

In 2008, Dr. Seuss was inducted into the California Hall of Fame. On March ii, 2009, the Web search engine Google temporarily changed its logo to commemorate Geisel's birthday (a practice that it often performs for diverse holidays and events).[68]

In 2004, U.S. children's librarians established the annual Theodor Seuss Geisel Laurels to recognize "the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding twelvemonth". Information technology should "demonstrate creativity and imagination to engage children in reading" from pre-kindergarten to second form.[69]

At Geisel's alma mater of Dartmouth, more than 90 percent of incoming start-year students participate in pre-matriculation trips run by the Dartmouth Outing Club into the New Hampshire wilderness. It is traditional for students returning from the trips to stay overnight at Dartmouth's Moosilauke Ravine Club, where they are served green eggs for breakfast. On April four, 2012, the Dartmouth Medical School was renamed the Audrey and Theodor Geisel Schoolhouse of Medicine in honour of their many years of generosity to the college.[seventy]

Dr. Seuss's honors include ii University Awards, ii Emmy Awards, a Peabody Honor, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal, the Inkpot Award[71] and the Pulitzer Prize.

Dr. Seuss has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at the 6500 block of Hollywood Boulevard.[72]

Dr. Seuss has been in Forbes ' list of the globe'south highest-paid expressionless celebrities every yr since 2001, when the list was kickoff published.

Pen names and pronunciations

Geisel's near famous pen proper name is regularly pronounced ,[three] an anglicized pronunciation inconsistent with his High german surname (the standard High german pronunciation is German language pronunciation: [ˈzɔʏ̯s]). He himself noted that it rhymed with "voice" (his own pronunciation being ). Alexander Laing, i of his collaborators on the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern,[73] wrote of it:

You're wrong as the deuce

And you shouldn't rejoice

If you're calling him Seuss.

He pronounces it Soice[74] (or Zoice)[75]

Geisel switched to the anglicized pronunciation considering information technology "evoked a effigy advantageous for an author of children's books to be associated with—Female parent Goose"[54] and because nearly people used this pronunciation. He added the "Md (abbreviated Dr.)" to his pen name because his father had always wanted him to practice medicine.[76]

For books that Geisel wrote and others illustrated, he used the pen proper name "Theo LeSieg", starting with I Wish That I Had Duck Feet published in 1965. "LeSieg" is "Geisel" spelled backward.[77] Geisel too published ane book under the name Rosetta Stone, 1975's Because a Piffling Bug Went Ka-Choo!!, a collaboration with Michael K. Frith. Frith and Geisel chose the name in honor of Geisel'southward second wife Audrey, whose maiden proper name was Stone.[78]

Political views

Geisel was a liberal Democrat and a supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.[ citation needed ] His early political cartoons prove a passionate opposition to fascism, and he urged action against information technology both before and after the Usa entered World War II.[79] His cartoons portrayed the fear of communism every bit overstated, finding greater threats in the House Commission on Unamerican Activities and those who threatened to cut the United States' "life line"[48] to Stalin and the USSR, whom he once depicted every bit a porter carrying "our war load".[47]

Dr. Seuss 1942 cartoon with the caption 'Waiting for the Point from Home'

Geisel supported the internment of Japanese Americans during World State of war II in order to prevent possible sabotage. Geisel explained his position:

Merely right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: "Brothers!" It is a rather flabby boxing cry. If we want to win, we've got to kill Japs, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy later on with those that are left.[80]

Later the war, Geisel overcame his feelings of animosity and re-examined his view, using his book Horton Hears a Who! (1954) equally an allegory for the American post-war occupation of Nippon,[81] too as dedicating the volume to a Japanese friend, though Ron Lamothe noted in an interview that fifty-fifty that book has a sense of "American chauvinism".[82]

In 1948, subsequently living and working in Hollywood for years, Geisel moved to La Jolla in San Diego, a predominantly Republican community.[83]

Geisel converted a copy of 1 of his famous children's books, Marvin K. Mooney Will Y'all Delight Go Now!, into a polemic presently before the end of the 1972–1974 Watergate scandal, in which United States president Richard Nixon resigned, by replacing the proper name of the main graphic symbol everywhere that information technology occurred.[84] "Richard Grand. Nixon, Will You lot Please Go Now!" was published in major newspapers through the cavalcade of his friend Art Buchwald.[84]

The line "a person'southward a person, no matter how small!!" from Horton Hears a Who! has been used widely every bit a slogan by the pro-life motion in the U.s.a.. Geisel and later his widow Audrey objected to this utilize; co-ordinate to her chaser, "She doesn't like people to hijack Dr. Seuss characters or textile to front their own points of view."[85] In the 1980s Geisel threatened to sue an anti-abortion grouping for using this phrase on their jotter, according to his biographer, causing them to remove it.[86] The chaser says he never discussed ballgame with either of them,[85] and the biographer says Geisel never expressed a public opinion on the discipline.[86] After Seuss's death, Audrey gave financial back up to Planned Parenthood.[87]

In his children's books

Geisel made a indicate of not starting time to write his stories with a moral in heed, stating that "kids can see a moral coming a mile off." He was not against writing about issues, still; he said that "there's an inherent moral in whatsoever story",[88] and he remarked that he was "subversive as hell."[89]

Geisel's books express his views on a remarkable variety of social and political issues: The Lorax (1971), almost environmentalism and anti-consumerism; The Sneetches (1961), near racial equality; The Butter Battle Book (1984), near the arms race; Yertle the Turtle (1958), about Adolf Hitler and anti-absolutism; How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), criticizing the economical materialism and consumerism of the Christmas season; and Horton Hears a Who! (1954), about anti-isolationism and internationalism.[54] [82]

In contempo times, Seuss's work for children has been criticized for presumably unconscious racist themes.[xc]

Poetic meters

Geisel wrote most of his books in anapestic tetrameter, a poetic meter employed by many poets of the English literary canon. This is often suggested as one of the reasons that Geisel's writing was so well received.[91] [92]

Anapestic tetrameter consists of 4 rhythmic units chosen anapests, each equanimous of two weak syllables followed by one potent syllable (the beat); often, the first weak syllable is omitted, or an additional weak syllable is added at the stop. An example of this meter can exist found in Geisel's "Yertle the Turtle", from Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories:

And today the Great Yertle, that Marvelous he

Is King of the Mud. That is all he can run across.[93]

Some books by Geisel that are written mainly in anapestic tetrameter as well contain many lines written in amphibrachic tetrameter wherein each strong syllable is surrounded by a weak syllable on each side. Hither is an instance from If I Ran the Circus:

All ready to put upward the tents for my circus.

I think I will call it the Circus McGurkus.

And Now comes an act of Due eastnormous Enormance!

No former performer's performed this performance!

Geisel besides wrote verse in trochaic tetrameter, an organisation of a strong syllable followed by a weak syllable, with iv units per line (for example, the title of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish). Traditionally, English language trochaic meter permits the final weak position in the line to be omitted, which allows both masculine and feminine rhymes.

Geisel generally maintained trochaic meter for only brief passages, and for longer stretches typically mixed it with iambic tetrameter, which consists of a weak syllable followed by a stiff, and is mostly considered easier to write. Thus, for case, the magicians in Bartholomew and the Oobleck brand their first appearance chanting in trochees (thus resembling the witches of Shakespeare's Macbeth):

Shuffle, duffle, muzzle, muff

They then switch to iambs for the oobleck spell:

Become brand the Oobleck tumble down

On every street, in every town![94]

Artwork

Geisel's early artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil drawings or watercolors, merely in his children's books of the postwar period, he generally fabricated use of a starker medium—pen and ink—ordinarily using simply black, white, and one or two colors. His later on books, such as The Lorax, used more colors.

Geisel's way was unique—his figures are often "rounded" and somewhat droopy. This is truthful, for instance, of the faces of the Grinch and the Cat in the Hat. Virtually all his buildings and machinery were devoid of straight lines when they were drawn, fifty-fifty when he was representing real objects. For example, If I Ran the Circus shows a droopy hoisting crane and a droopy steam calliope.

Geisel manifestly enjoyed cartoon architecturally elaborate objects, and a number of his motifs are identifiable with structures in his childhood domicile of Springfield, including examples such as the onion domes of its Main Street and his family's brewery.[95] His endlessly varied only never rectilinear palaces, ramps, platforms, and gratuitous-standing stairways are among his most evocative creations. Geisel also drew circuitous imaginary machines, such equally the Audio-Telly-O-Tally-O-Count, from Dr. Seuss'southward Sleep Book, or the "near peculiar machine" of Sylvester McMonkey McBean in The Sneetches. Geisel as well liked drawing outlandish arrangements of feathers or fur: for instance, the 500th hat of Bartholomew Cubbins, the tail of Gertrude McFuzz, and the pet for girls who like to brush and comb, in 1 Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.

Geisel's illustrations often convey movement vividly. He was fond of a sort of "voilà" gesture in which the hand flips outward and the fingers spread slightly astern with the thumb upward. This motility is done by Ish in Ane Fish, Two Fish, Crimson Fish, Blue Fish when he creates fish (who perform the gesture with their fins), in the introduction of the various acts of If I Ran the Circus, and in the introduction of the "Trivial Cats" in The Cat in the Hat Comes Dorsum. He was likewise addicted of drawing easily with interlocked fingers, making it look as though his characters were twiddling their thumbs.

Geisel besides follows the drawing tradition of showing motion with lines, like in the sweeping lines that back-trail Sneelock'due south final dive in If I Ran the Circus. Cartoon lines are also used to illustrate the action of the senses—sight, smell, and hearing—in The Big Brag, and lines even illustrate "idea", as in the moment when the Grinch conceives his awful program to ruin Christmas.

Recurring images

Geisel's early work in advertising and editorial cartooning helped him to produce "sketches" of things that received more than perfect realization later on in his children'southward books. Often, the expressive utilize to which Geisel put an image, after on, was quite different from the original.[96] Hither are some examples:

- An editorial drawing from July 16, 1941[97] depicts a whale resting on the top of a mount as a parody of American isolationists, peculiarly Charles Lindbergh. This was later rendered (with no apparent political content) as the Wumbus of On Across Zebra (1955). Seussian whales (cheerful and airship-shaped, with long eyelashes) too occur in McElligot's Pool, If I Ran the Circus, and other books.

- Some other editorial drawing from 1941[98] shows a long cow with many legs and udders representing the conquered nations of Europe existence milked past Adolf Hitler. This later became the Umbus of On Beyond Zebra.

- The tower of turtles in a 1942 editorial cartoon[99] prefigures a like tower in Yertle the Turtle. This theme besides appeared in a Judge drawing as 1 letter of the alphabet of a hieroglyphic message, and in Geisel's curt-lived comic strip Hejji. Geisel once stated that Yertle the Turtle was Adolf Hitler.[100]

- Footling cats A, B, and C (besides as the residuum of the alphabet) who leap from each other'south hats appeared in a Ford Motor Visitor ad.

- The connected beards in Did I E'er Tell Yous How Lucky You lot Are? appear oftentimes in Geisel'due south work, most notably in Hejji, which featured ii goats joined at the beard, The v,000 Fingers of Dr. T., which featured two roller-skating guards joined at the beard, and a political cartoon in which Nazism and the America First motility are portrayed as "the men with the Siamese Beard".

- Geisel'south earliest elephants were for advertising and had somewhat wrinkly ears, much as existent elephants do.[101] With And to Call back That I Saw It on Mulberry Street! (1937) and Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), the ears became more than stylized, somewhat like angel wings and thus advisable to the saintly Horton. During Earth War II, the elephant image appeared as an emblem for India in four editorial cartoons.[102] Horton and similar elephants appear often in the postwar children's books.

- While drawing advertisements for Waltz, Geisel became good at drawing insects with huge stingers,[103] shaped similar a gentle South-curve and with a sharp end that included a rearward-pointing barb on its lower side. Their facial expressions draw gleeful malevolence. These insects were later rendered in an editorial cartoon as a swarm of Centrolineal aircraft[104] (1942), and again equally the Sneedle of On Beyond Zebra, and however again as the Skritz in I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew.

- There are many examples of creatures who adapt themselves in repeating patterns, such as the "Ii and fro walkers, who march in five layers", and the Through-Horns Jumping Deer in If I Ran the Circus, and the arrangement of birds which the protagonist of Oh, the Places You lot'll Go! walks through, as the narrator admonishes him to "... ever be dexterous and deft, and never mix upwards your right foot with your left."

Bibliography

Publications

Geisel wrote more than threescore books over the course of his long career. Well-nigh were published under his well-known pseudonym Dr. Seuss, though he likewise authored more than a dozen books as Theo LeSieg and i as Rosetta Stone. His books have topped many bestseller lists, sold over 600 million copies, and been translated into more than 20 languages.[7] In 2000, Publishers Weekly compiled a listing of the best-selling children's books of all time; of the top 100 hardcover books, 16 were written past Geisel, including Green Eggs and Ham, at number 4, The Cat in the Hat, at number 9, and 1 Fish, Ii Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish, at number 13.[105] In the years after his death in 1991, two additional books were published based on his sketches and notes: Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! and Daisy-Head Mayzie. My Many Colored Days was originally written in 1973 but was posthumously published in 1996. In September 2011, seven stories originally published in magazines during the 1950s were released in a collection titled The Bippolo Seed and Other Lost Stories.[106]

Geisel also wrote a pair of books for adults: The Seven Lady Godivas (1939; reprinted 1987), a retelling of the Lady Godiva legend that included nude depictions; and Yous're But Old Once! (written in 1986 when Geisel was 82), which chronicles an old man'south journey through a clinic. His concluding book was Oh, the Places You'll Go!, which was published the year before his death and became a popular gift for graduating students.[107]

Selected titles

- And to Recollect That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937)

- Horton Hatches the Egg (1940)

- Horton Hears a Who (1954)

- The Cat in the Lid (1957)

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957)

- The Cat in the Hat Comes Dorsum (1958)

- One Fish 2 Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1960)

- Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

- The Sneetches and Other Stories (1961)

- Hop on Popular (1963)

- Play a joke on in Socks (1965)

- The Lorax (1971)

- The Butter Battle Book (1981)

- I Am Not Going to Go Upward Today! (1987)

- Oh, the Places You'll Become! (1990)

Retired books

Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the organization that owns the rights to the books, films, TV shows, stage productions, exhibitions, digital media, licensed merchandise, and other strategic partnerships, appear on March 2, 2021, that information technology will stop publishing and licensing six books. The publications include And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937), If I Ran the Zoo (1950), McElligot's Pool (1947), On Beyond Zebra! (1955), Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953) and The Cat's Quizzer (1976). According to the organization, the books "portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong" and are no longer existence published due to racist and insensitive imagery.[108]

Listing of screen adaptations

Theatrical short films

| Year | Title | Format | Manager | Distributor | Length | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Horton Hatches the Egg | traditional blitheness | Bob Clampett | Warner Bros. Pictures | 10 min. | [109] |

| 1943 | The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins | terminate motion | George Pal | Paramount Pictures | [110] | |

| 1944 | And to Recollect That I Saw It on Mulberry Street | [111] | ||||

| 1950 | Gerald McBoing-Boing | traditional animation | Robert Cannon | UPA and Columbia Pictures | [112] |

Theatrical feature films

| Year | Championship | Format | Director(southward) | Distributor | Length | Upkeep | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. | live-action | Roy Rowland | Columbia Pictures | 92 min. | [113] | |

| 2000 | How the Grinch Stole Christmas | Ron Howard | Universal Pictures | 104 min. | $123 million | [114] | |

| 2003 | The Cat in the Hat | Bo Welch | Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures | 82 min. | $109 million | [115] | |

| 2008 | Horton Hears a Who! | computer animation | Jimmy Hayward & Steve Martino | 20th Century Fob | 86 min. | $85 million | [116] |

| 2012 | The Lorax | Chris Renaud and Kyle Balda | Universal Pictures | $70 million | [117] | ||

| 2018 | The Grinch | Scott Mosier and Yarrow Cheney | 90 min. | $75 1000000 | [118] |

Television receiver specials

| Year | Title | Format | Studio | Director | Writer | Distributor | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | How the Grinch Stole Christmas! | traditional animation | Chuck Jones Productions | Chuck Jones | Dr. Seuss, Irv Spector, and Bob Ogle | MGM | 25 min. |

| 1970 | Horton Hears a Who! | Dr. Seuss | |||||

| 1971 | The Cat in the Chapeau | DePatie-Freleng Enterprises | Hawley Pratt | CBS | |||

| 1972 | The Lorax | ||||||

| 1973 | Dr. Seuss on the Loose | ||||||

| 1975 | The Hoober-Bloob Highway | Alan Zaslove | |||||

| 1977 | Halloween Is Grinch Nighttime | Gerard Baldwin | ABC | ||||

| 1980 | Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You? | ||||||

| 1982 | The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat | Neb Perez | |||||

| 1989 | The Butter Battle Book | Bakshi Production | Ralph Bakshi | Turner | |||

| 1995 | Daisy-Head Mayzie | Hanna-Barbera Productions | Tony Collingwood |

Goggle box series

| Yr | Title | Format | Director | Author | Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–1998 | The Wubbulous World of Dr. Seuss | live-action/boob | Various | Various | Nickelodeon |

| 2010–2018 | The Cat in the Chapeau Knows a Lot Most That! | traditional animation | Treehouse Tv set | ||

| 2019–present | Dark-green Eggs and Ham | Netflix |

Adaptations

For most of his career, Geisel was reluctant to have his characters marketed in contexts outside of his own books. However, he did allow the creation of several animated cartoons, an fine art form in which he had gained experience during Globe War II, and he gradually relaxed his policy every bit he aged.

The starting time adaptation of one of Geisel's works was a cartoon version of Horton Hatches the Egg, animated at Warner Bros. in 1942 and directed by Bob Clampett. Information technology was presented as part of the Merrie Melodies series and included a number of gags not present in the original narrative, including a fish committing suicide and a Katharine Hepburn imitation past Mayzie.

As part of George Pal's Puppetoons theatrical cartoon series for Paramount Pictures, ii of Geisel's works were adapted into terminate-move films by George Pal. The outset, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, was released in 1943.[119] The second, And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street, with a title slightly altered from the volume's, was released in 1944.[120] Both were nominated for an University Award for "Short Subject (Cartoon)".

In 1959, Geisel authorized Revell, the well-known plastic model-making visitor, to make a series of "animals" that snapped together rather than being glued together, and could be assembled, disassembled, and re-assembled "in thousands" of ways. The series was called the "Dr. Seuss Zoo" and included Gowdy the Dowdy Grackle, Norval the Bashful Blinket, Tingo the Noodle Topped Stroodle, and Roscoe the Many Footed Panthera leo. The bones body parts were the same and all were interchangeable, and so information technology was possible for children to combine parts from various characters in essentially unlimited ways in creating their own animal characters (Revell encouraged this by selling Gowdy, Norval, and Tingo together in a "Gift Set" as well as individually). Revell also made a conventional glue-together "beginner's kit" of The Cat in the Hat.

In 1966, Geisel authorized eminent drawing artist Chuck Jones—his friend and old colleague from the war—to make a cartoon version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! Geisel was credited as a co-producer under his existent name Ted Geisel, along with Jones. The cartoon was narrated by Boris Karloff, who besides provided the voice of the Grinch. It was very faithful to the original volume and is considered a archetype to this day by many. It is often broadcast as an annual Christmas tv special. Jones directed an adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! in 1970 and produced an accommodation of The Cat in the Chapeau in 1971.

From 1972 to 1983, Geisel wrote six animated specials that were produced by DePatie-Freleng: The Lorax (1972); Dr. Seuss on the Loose (1973); The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975); Halloween Is Grinch Night (1977); Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You? (1980); and The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Chapeau (1982). Several of the specials won multiple Emmy Awards.

A Soviet paint-on-glass-animated brusque motion picture was made in 1986 called Welcome, an accommodation of Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. The concluding adaptation of Geisel's work before he died was The Butter Battle Book, a goggle box special based on the book of the same proper name, directed by Ralph Bakshi.

A television film titled In Search of Dr. Seuss was released in 1994, which adjusted many of Seuss's stories. It uses both live-action versions and animated versions of the characters and stories featured; however, the animated portions were merely edited versions of previous animated television specials and, in some cases, re-dubbed too.

After Geisel died of cancer at the historic period of 87 in 1991, his widow Audrey Geisel took charge of licensing matters until her death in 2018. Since then, licensing is controlled by the nonprofit Dr. Seuss Enterprises. Audrey approved a live-action feature-film version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas starring Jim Carrey, as well as a Seuss-themed Broadway musical called Seussical, and both premiered in 2000. The Grinch has had express engagement runs on Broadway during the Christmas season, after premiering in 1998 (under the title How the Grinch Stole Christmas) at the Sometime Globe Theatre in San Diego, where it has get a Christmas tradition. In 2003, another live-activity film was released, this fourth dimension an adaptation of The True cat in the Hat that featured Mike Myers as the title grapheme. Audrey Geisel spoke critically of the picture show, especially the casting of Myers as the Cat in the Lid, and stated that she would not allow whatsoever further live-action adaptations of Geisel's books.[121] However, a get-go animated CGI feature picture adaptation of Horton Hears a Who! was approved, and was eventually released on March xiv, 2008, to positive reviews. A 2nd CGI-animated feature film adaptation of The Lorax was released past Universal on March 2, 2012 (on what would have been Seuss's 108th birthday). The tertiary adaptation of Seuss'south story, the CGI-animated feature film, The Grinch, was released by Universal on November 9, 2018.

Five television series have been adapted from Geisel's piece of work. The beginning, Gerald McBoing-Boing, was an animated telly adaptation of Geisel's 1951 cartoon of the same name and lasted three months between 1956 and 1957. The second, The Wubbulous World of Dr. Seuss, was a mix of live-activity and puppetry past Jim Henson Television, the producers of The Muppets. It aired for two seasons on Nickelodeon in the United States, from 1996 to 1998. The tertiary, Gerald McBoing-Boing, is a remake of the 1956 series.[122] Produced in Canada past Cookie Jar Entertainment (at present DHX Media) and Due north America by Classic Media (now DreamWorks Classics), it ran from 2005 to 2007. The fourth, The Cat in the Lid Knows a Lot Nearly That!, produced by Portfolio Entertainment Inc., began on August 7, 2010, in Canada and September 6, 2010, in the United States and is producing new episodes as of 2018[update]. The 5th, Greenish Eggs and Ham, is an blithe streaming television adaptation of Geisel'southward 1960 book of the same title and premiered on November viii, 2019, on Netflix,[123] [124] [125] [126] [127] and a second season by the title of Green Eggs and Ham: The 2nd Serving is scheduled to premiere in 2021.[128] [129]

Geisel's books and characters are also featured in Seuss Landing, one of many islands at the Islands of Adventure theme park in Orlando, Florida. In an effort to match Geisel'southward visual mode, there are reported "no directly lines" in Seuss Landing.[130]

The Hollywood Reporter has reported that Warner Animation Group and Dr. Seuss Enterprises accept struck a deal to brand new blithe movies based on the stories of Dr. Seuss. Their first project will be a fully blithe version of The True cat in the Hat.[131]

Encounter also

- The Cat in the Hat (play)

- "The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite" – a 1992 R.E.M. vocal referencing a reading from Seuss.

- Origins of a Story

References

- ^ "The Beginnings of Dr. Seuss".

- ^ "How to Mispronounce "Dr. Seuss"". Information technology is truthful that the centre name of Theodor Geisel—"Seuss," which was also his mother'due south maiden name—was pronounced "Zoice" by the family, and by Theodor Geisel himself. So, if you lot are pronouncing his full given name, maxim "Zoice" instead of "Soose" would not exist wrong. Yous'd have to explicate the pronunciation to your listener, simply you would be pronouncing information technology as the family did.

- ^ a b "Seuss". Random House Unabridged Lexicon.

- ^ a b pronunciation of "Geisel" and "Seuss" in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ^ "Near the Author, Dr. Seuss, Seussville". Timeline. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved February fifteen, 2012.

- ^ "Seuss on New Zealand Idiot box, 1964".

- ^ a b Bernstein, Peter West. (1992). "Unforgettable Dr. Seuss". Unforgettable. Reader'due south Assimilate Australia: 192. ISSN 0034-0375.

- ^ "Theodor Seuss Geisel" (2015). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss". Emmys.com . Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c Mandeville Special Collections Library. "The Dr. Seuss Collection". UC San Diego. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved April x, 2012.

- ^ Geisel, Theodor Seuss (2005). "Dr. Seuss Biography". In Taylor, Constance (ed.). Theodor Seuss Geisel The Early Works of Dr. Seuss. Vol. 1. Miamisburg, OH: Checker Volume Publishing Group. p. six. ISBN978-1-933160-01-six.

- ^ Springfield (Mass.) (1912). Municipal register of the city of Springfield (Mass.) . Retrieved December 29, 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Who Knew Dr. Seuss Could Brew?". Narragansett Beer. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on Feb viii, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Mulberry Street". Seuss in Springfield. March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ Pease, Donald (2011). "Dr. Seuss in Ted Geisel'due south Never-Never Land". PMLA. 126 (1): 197–202. doi:10.1632/pmla.2011.126.ane.197. JSTOR 41414092. S2CID 161957666.

- ^ Scholl, Travis (March 2, 2012). "Happy birthday, Dr. Seuss!". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Minear (1999), p. ix.

- ^ Nell, Phillip (March–Apr 2009). "Impertient Questions". Humanities. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

- ^ Morgan, Judith; Morgan, Neil (1996). Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: a biography . p. 36. ISBN978-0-306-80736-7 . Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ^ Fensch, Thomas (2001). The Man Who Was Dr. Seuss. Woodlands: New Century Books. p. 38. ISBN978-0-930751-11-i.

- ^ a b c d Pace, Eric (September 26, 1991). "Dr. Seuss, Modern Mother Goose, Dies at 87". The New York Times. New York City. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "Famous Lincoln Alumni". Lincoln College, Oxford. Archived from the original on Jan 30, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 57

- ^ Pease (2010), pp. 41–42

- ^ Cohen (2004), pp. 72–73

- ^ Morgan (1995), pp. 59–62

- ^ Cohen (2004), p. 86

- ^ Cohen (2004), p. 83

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 65

- ^ a b Pease (2010), pp. 48–49

- ^ Pease (2010), p. 49

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 79

- ^ Levine, Stuart P. (2001). Dr. Seuss. San Diego, CA: Lucent Books. ISBN978-1560067481. OCLC 44075999.

- ^ Morgan (1995), pp. 71–72

- ^ Baker, Andrew (March 3, 2010). "Ten Things You May Not Have Known Most Dr. Seuss". The Peel. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Nel (2004), pp. 119–21

- ^ Lurie, Alison (1992). The Chiffonier of Dr. Seuss. Popular Culture: An Introductory Text. ISBN978-0879725723 . Retrieved Oct 30, 2013.

- ^ Morgan (1995), pp. 79–85

- ^ Richard H. Minear, Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World State of war II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel p. 16. ISBN ane-56584-704-0

- ^ Minear, Richard H. (1999). Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The Globe War Ii Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisell. New York Urban center: The New Press. p. 9. ISBN978-1-56584-565-7.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (February xiii, 1942). "Waiting for the Signal from Habitation".

- ^ Nel, Philip (2007). "Children's Literature Goes to State of war: Dr. Seuss, P. D. Eastman, Munro Leaf, and the Private SNAFU Films (1943–46)". The Periodical of Popular Culture. 40 (3): 478. doi:ten.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00404.x. ISSN 1540-5931.

For example, Seuss'due south back up of civil rights for African Americans appears prominently in the PM cartoons he created before joining ''Fort Fox.

- ^ Vocalist, Saul Jay. "Dr. Seuss And The Jews". Retrieved Dec 23, 2019.

- ^ Mandeville Special Collections Library. "Congress". Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss. UC San Diego. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ Mandeville Special Collections Library. "Republican Party". Dr. Seuss Went to State of war: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss. UC San Diego. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved Apr 10, 2012.

- ^ Minear (1999), p. 191.

- ^ a b Mandeville Special Collections Library. "Feb 19". Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss. UC San Diego. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved Apr 10, 2012.

- ^ a b Mandeville Special Collections Library. "March 11". Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss. UC San Diego. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved Apr x, 2012.

- ^ Minear (1999), pp. 190–91.

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 116

- ^ Morgan (1995), pp. 119–twenty

- ^ Ellin, Abby (October 2, 2005). "The Return of Gerlad McBoing Boing?". The New York Times.

- ^ Kahn Jr., E. J. (December 17, 1960). "Profiles: Children's Friend". The New Yorker. Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c Menand, Louis (Dec 23, 2002). "Cat People: What Dr. Seuss Really Taught Us". The New Yorker. Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved September sixteen, 2008.

- ^ Roback, Diane (March 22, 2010). "The Reign Continues". Publishes Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded to Eleven", Dartmouth Alumni Magazine July 1955, p. 18-nineteen

- ^ "A Day of Ceremony", Dartmouth Medicine: The Magazine of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Fall 2012

- ^ Tanya Anderson, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel), ISBN 143814914X, due north.p.

- ^ "To Tell the Truth Primetime Episode Guide 1956–67". "To Tell the Truth" on the Web . Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c Wadler, Joyce (Nov 29, 2000). "Public Lives: Mrs. Seuss Hears a Who, and Tells About It". The New York Times . Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "Audrey Geisel, caretaker of the Dr. Seuss literary estate, dies at 97". The Washington Postal service. December 19, 2018. Retrieved Dec 22, 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees | Whittier College". world wide web.whittier.edu . Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Laura Ingalls Wilder Honour, Past winners. Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) – American Library Association (ALA). Most the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "Special Awards and Citations". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Gorman, Tom; Miles Corwin (September 26, 1991). "Theodor Geisel Dies at 87; Wrote 47 Dr. Seuss Books, Author: His last new work, 'Oh, the Places You'll Get!' has proved popular with executives equally well every bit children". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "About the Geisel Library Building". UC San Diego. Archived from the original on Jan 2, 2014. Retrieved April ten, 2012.

- ^ Mandeville Special Collections Library. "Annals of Hans Suess Papers 1875–1989". UC San Diego. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Google Vacation Logos". 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to the (Theodor Seuss) Geisel Award domicile folio!". ALSC. ALA.

"Theodor Seuss Geisel Award". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved June 17, 2013. - ^ "Dartmouth Names Medical School in Honor of Audrey and Theodor Geisel". Geisel School of Medicine. April iv, 2012. Retrieved Apr 9, 2012.

- ^ "Inkpot Honor".

- ^ Corwin, Miles; Gorman, Tom (September 26, 1991). "Dr. Seuss – Hollywood Star Walk". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "And to Think That Information technology Happened at Dartmouth". now.dartmouth.edu. 2010. Archived from the original on Apr 12, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa (December xviii, 2009). "Theodor Seuss Geisel: Author Study". anapsid.org . Retrieved Dec 2, 2011. (Source in PDF.)

- ^ "About the Author, Dr. Seuss, Seussville". Biography. Archived from the original on December vi, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "15 Things Y'all Probably Didn't Know About Dr. Seuss". Thefw.com. Retrieved Dec 16, 2013.

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 219

- ^ Morgan (1995), p. 218

- ^ Macdonald, Fiona. "The surprisingly radical politics of Dr Seuss". world wide web.bbc.com . Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ Minear (1999), p. 184.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!". Open Civilization. August xx, 2014. Retrieved Jan vii, 2019.

- ^ a b Forest, Hayley and Ron Lamothe (interview) (August 2004). "Interview with filmmaker Ron Lamothe about The Political Dr. Seuss". MassHumanities eNews. Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. Archived from the original on September xvi, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Lamothe, Ron (October 27, 2004). "PBS Independent Lens: The Political Dr. Seuss". The Washington Post . Retrieved Apr x, 2012.

- ^ a b Buchwald, Art (July thirty, 1974). "Richard Grand. Nixon Will Y'all Please Get Now!". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ a b "In 'Horton' Moving picture, Abortion Foes Hear an Ally". NPR. March xiv, 2008. Retrieved January vii, 2019.

- ^ a b Baram, Marcus (March 17, 2008). "Horton'due south Who: The Unborn?". ABC News . Retrieved January seven, 2019.

- ^ "Who Would Dr. Seuss Support?". Cosmic Exchange. Jan 2, 2004. Retrieved Jan 7, 2019.

- ^ Bunzel, Peter (April 6, 1959). "The Wacky World of Dr. Seuss Delights the Kid—and Adult—Readers of His Books". Life. Chicago. ISSN 0024-3019. OCLC 1643958.

Virtually of Geisel's books point a moral, though he insists that he never starts with 1. 'Kids,' he says, 'can come across a moral coming a mile off and they gag at information technology. Just there's an inherent moral in any story.'

- ^ Cott, Jonathan (1984). "The Skillful Dr. Seuss". Pipers at the Gates of Dawn: The Wisdom of Children's Literature (Reprint ed.). New York Urban center: Random House. ISBN978-0-394-50464-3. OCLC 8728388.

- ^ Katie Ishizuka, Ramón Stephens (2019). "The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Black, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books". Research on Diversity in Youth Literature.

- ^ Mensch, Betty; Freeman, Alan (1987). "Getting to Solla Sollew: The Existentialist Politics of Dr. Seuss". Tikkun: thirty.

In opposition to the conventional—indeed, hegemonic—iambic vox, his metric triplets offer the power of a more key chant that speedily draws the reader in with relentless repetition.

- ^ Fensch, Thomas, ed. (1997). Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN978-0-7864-0388-ii. OCLC 37418407.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (1958). Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories. Random House. OCLC 18181636.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (1949). Bartholomew and the Oobleck . Random House. OCLC 391115.

- ^ "Seussified Springfield". Hell's Acres. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019.

- "And to Call up that He Saw It in Springfield!". Springfield Museums. August two, 2011. Archived from the original on August nineteen, 2016.

- ^ "Mandeville Special Collections Library". UC San Diego. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (July xvi, 1941). "The Isolationist". Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (May nineteen, 1941). "The caput eats.. the balance gets milked". Archived from the original on Apr 17, 2012. Retrieved April ix, 2012.

- ^ Dr. Seuss (March 21, 1942). "You can't build a substantial V out of turtles!". Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Roberts, Chuck (Oct 17, 1999). "Serious Seuss: Children's author as political cartoonist". CNN . Retrieved Apr 9, 2012.

- ^ Geisel, Theodor. "Yous tin't kill an elephant with a pop gun!". L.P.C.Co. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ Geisel, Theodor. "Bharat Listing". Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Geisel, Theordor. "Flit kills!". [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ Theodor Geisel (Nov xi, 1942). "Effort and pull the wings off these butterflies, Benito!". Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April ix, 2012.

- ^ Turvey, Debbie Hochman (December 17, 2001). "All-Time Bestselling Children'south Books". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on Apr 6, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ "Random Uncovers 'New' Seuss Stories". Publishers Weekly . Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Blais, Jacqueline; Memmott, Carol; Minzesheimer, Bob (May sixteen, 2007). "Book buzz: Dave Barry really rocks". U.s.a. Today . Retrieved Jan 17, 2012.

- ^ Feldman, Kate (March 2, 2021). "Six Dr. Seuss books to stop existence published over 'hurtful and incorrect' portrayals". New York Daily News . Retrieved March two, 2021.

- ^ "Horton Hatches the Egg". Turner Classic Movies . Retrieved March half-dozen, 2021.

- ^ "The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins". MUBI . Retrieved March half dozen, 2021.

- ^ "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street". Turner Classic Movies . Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Gerlad McBong=Boing". Turner Classic Movies . Retrieved March half dozen, 2021.

- ^ "The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T". Turner Archetype Movies . Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2010)". Box Part Mojo. Cyberspace Movie Database (IMDb). due north.d. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ "The Cat in the Hat (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database (IMDb). due north.d. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss' Horton Hears a Who! (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Cyberspace Flick Database (IMDb). northward.d. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss' The Lorax (2012)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Pic Database (IMDb). n.d. Retrieved Nov 24, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss' The Grinch (2018)". Box Office Mojo. Net Movie Database (IMDb). due north.d. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ "The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins". IMDb . Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Large Cartoon Database". Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Associated Press (Feb 26, 2004). Seussentenial: 100 years of Dr. Seuss. MSNBC. Retrieved on Apr half dozen, 2008.

- ^ Ellin, Abby (October ii, 2005). "The Return of ... Gerald McBoing Boing?". The New York Times . Retrieved Apr 7, 2008.

- ^ Flook, Ray (Feb xix, 2019). "'Light-green Eggs and Ham': Netflix's Blithe Series Serves Up Teaser, Vocalisation Cast". Haemorrhage Absurd News . Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (April 29, 2015). "Netflix Picks Upwards 'Light-green Eggs and Ham' Animated Series From Ellen DeGeneres". Borderline Hollywood . Retrieved December xx, 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (Apr 6, 2018). "Jared Stern Inks Overall Bargain With Warner Bros. Telly". Deadline Hollywood . Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ "Green Eggs and Ham | Read by Michael Douglas, Adam Devine & More than! | Netflix". YouTube Netflix Official. October viii, 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Netflix's Light-green Eggs and Ham Series Sets Premiere Date". ComingSoon.cyberspace. Oct 8, 2019. Retrieved October eleven, 2019.

- ^ Petski, Denise (Dec 20, 2019). "'Green Eggs And Ham' Renewed For Season 2 By Netflix". Deadline Hollywood . Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ "Light-green Eggs & Ham Season 2: Delayed? When Will It Release? All the Latest Details!". Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ Universal Orlando.com. The True cat in the Hat ride Archived April x, 2008, at the Wayback Motorcar. Retrieved on April 6, 2008.

- ^ Kit, Borys; Fernandez, Jay A. (January 24, 2018). "New 'Cat in the Hat' Movie in the Works From Warner Bros". The Hollywood Reporter.

Farther reading

- Cohen, Charles (2004). The Seuss, the Whole Seuss and Zilch But the Seuss: A Visual Biography of Theodor Seuss Geisel. Random Firm Books for Immature Readers. ISBN978-0-375-82248-3. OCLC 53075980.

- Fensch, Thomas, ed. (1997). Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss: Essays on the Writings and Life of Theodor Geisel. McFarland & Company. ISBN978-0-7864-0388-2.

- Geisel, Audrey (1995). The Secret Art of Dr. Seuss. Random House. ISBN978-0-679-43448-1.

- Geisel, Theodor (1987). Dr. Seuss from So to At present: A Catalogue of the Retrospective Exhibition. Random House. ISBN978-0-394-89268-9.

- Geisel, Theodor (2001). Minnear, Richard (ed.). Dr. Seuss Goes to State of war: The World State of war II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel. New Press. ISBN978-one-56584-704-0.

- Geisel, Theodor (2004). The Ancestry of Dr. Seuss: An Informal Reminiscence. Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Geisel, Theodor Seuss (2005). Theodor Seuss Geisel: The Early on Works, Volume i. Checker Volume Publishing. ISBN978-1-933160-01-6.

- Geisel, Theodor (1987). Minnear, Richard (ed.). The Tough Coughs as He Ploughs the Dough: Early Writings and Cartoons past Dr. Seuss. New York: Morrow/Remco Worldservice Books. ISBN978-0-688-06548-5.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2019). Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imaginationc. Dutton. ISBN978-1524742782.

- Lamothe, Ron (2004). The Political Dr. Seuss (DVD). Terra Incognita Films. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved Jan iii, 2009. Documentary aired on the Public Television Organization.

- Lathem, Edward Connery (2000). Who's Who and What's What in the Books of Dr. Seuss. Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- MacDonald, Ruth K. (1988). Dr. Seuss . Twayne Publishers. ISBN978-0-8057-7524-2.

- Morgan, Judith; Morgan, Neil (1995). Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel. Random Business firm. ISBN978-0-679-41686-9.

- Nel, Philip (2007). The Annotated Cat: Nether the Hats of Seuss and His Cats. Random House. ISBN978-0-375-83369-4.

- Nel, Philip (2004). Dr. Seuss: American Icon . Continuum Publishing. ISBN978-0-8264-1434-2.

- Pease, Donald E. (2010). Theodor Seuss Geisel . Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-nineteen-532302-3.

- Weidt, Maryann; Maguire, Kerry (1994). Oh, the Places He Went. Carolrhoda Books. ISBN978-0-87614-627-nine.

External links

- Seussville site Random House

- Dr. Seuss at the Internet Broadway Database

- Dr. Seuss at Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Dr. Seuss biography on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss

- The Advertising Artwork of Dr. Seuss

- The Register of Dr. Seuss Collection UC San Diego

- Hotchkiss, Eugene III (Bound 2004). "Dr. Seuss Keeps Me Guessing: A Commencement story past President Emeritus Eugene Hotchkiss III". lakeforest.edu. Archived from the original on Baronial xiv, 2004. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Dr. Seuss / Theodor Geisel artwork can be viewed at American Art Archives spider web site

- Dr. Seuss at IMDb

- The Dr. Seuss That Switched His Voice – poem by Joe Dolce, get-go published in Quadrant magazine.

- Register of the Dr. Seuss Collection, UC San Diego

- Dr. Seuss at Library of Congress Regime, with 190 catalog records

- Theodor Seuss Geisel (real name), Theo. LeSieg (pseud.), and Rosetta Stone (joint pseud.) at LC Authorities with 30, nine, and ane records

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Seuss

0 Response to "Dr Seuss Clip Art Cat in the Hat Dr Seuss Cartoon Characters Drawings of Portait"

Post a Comment